This month again we have two runners-up. In no particular order, as always, they are Levant Tin Mine Stack by Joyce Macadam:

The placement of the stack in the composition is what is important here. There is always something poignant, I think, about ruins by the sea, such as the pollarded columns of Roman temples that can be seen at various places on the coast in Libya. In fact this particular mine went nearly two miles out under the sea, according to Wikipedia, so the impression that the stack is somehow stranded on the coast is misleading: it is really an example of engineering ingenuity.

Talking of great engineering, our other runner-up photo was The 4.50 from Paddington by Richardr.

Richardr captures the elegance as well as the grandeur of Brunel's great structure, and reanimates the cliche that such buildings were the cathedrals of their age. Personally, this picture reminds me happily of one of my favourite novels, Austerlitz by WG Sebald (named not for the battle but for the Parisian station). Sebald habitually used photographs in his fiction - although grainy ones that he degraded by photocopying them, rather than the pellucid image that Richardr has achieved here.

Our winner this month is Ouse Bridge from Skeldergate Bridge by woodytyke:

What the judges particularly admired about this picture was the light (the reflection of the white rails on the left is like a Sisley painting) as well as the splendid panorama. There is a tremendous amount of historical information in this picture, and I can imagine a future historian finding it a rich source. The photographs in the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments series provide an important historical record (supplemented by expert commentary and drawn plans) but the many photographs being taken now, attested in a small way by the BHO Flickr group, will provide far more detailed evidence.

As I announced on the group page, we're going to run together November and December and pick a winner in January. The reason for this is that in December no one will be in the office with the technical savvy to be able to upload a winning picture to the homepage. But please do keep adding your photos to the group!

British History Online is the digital library containing some of the core printed primary and secondary sources for the medieval and modern history of the British Isles.

Thursday, 21 November 2013

Friday, 25 October 2013

September photo competition

It is no reflection on the quality of submissions for September, but this month we only had one runner up (it's to do with the way the number of votes fall).

Our runner up is by a stalwart of the Flickr competition, Richardr, and is The Jesus of Lubeck:

This ship had an interesting, if not very creditable, history, being used first by the Hanseatic League and then bought by Henry VIII. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography says, in the entry for Sir John Hawkins:

The ship was used by Hawkins for his activities in slaving trades, activities which seem to have descended on occasion to gangsterism:

Our winner this month is Stott Park Bobbin Mill - the main workshop by the-frantic photographer:

It's difficult to get a scene as cluttered as this into an effectively composed picture. I think what particularly works here is the tension between the order of an efficient workshop and the requirements of the place: there is a lot of stuff here, but nothing is out of place. The large windows are important too, in humanising the space: despite it being empty there is still an impression of bustle.

Our runner up is by a stalwart of the Flickr competition, Richardr, and is The Jesus of Lubeck:

This ship had an interesting, if not very creditable, history, being used first by the Hanseatic League and then bought by Henry VIII. The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography says, in the entry for Sir John Hawkins:

Hawkins, possibly using his connections with the court through west-country gentry like the Carews, managed to get the queen's backing. He was allowed to charter one of the largest ships in her navy, the 700 ton Jesus of Lubeck, purchased from the Hanseatic port under Henry VIII (but now riddled with dry rot), and to sail under the royal standard.

The ship was used by Hawkins for his activities in slaving trades, activities which seem to have descended on occasion to gangsterism:

After lading a cargo of hides at Curaçao, which he left on 15 May, Hawkins traded profitably at Rio de la Hacha, after again using force to dictate slave prices.One thing I like about this picture is the bricks reflected in the glass above the ship - bricks which, I imagine, are older than the painting itself.

Our winner this month is Stott Park Bobbin Mill - the main workshop by the-frantic photographer:

It's difficult to get a scene as cluttered as this into an effectively composed picture. I think what particularly works here is the tension between the order of an efficient workshop and the requirements of the place: there is a lot of stuff here, but nothing is out of place. The large windows are important too, in humanising the space: despite it being empty there is still an impression of bustle.

Thursday, 3 October 2013

August photo competition

Somewhat belatedly, following a couple of weeks off in September, I am able to blog about the winner and runners-up of our August photo competition. The judges thought this was a particularly strong month, so thanks to everybody who added photos to the group - and please keep doing so!

We had four runners-up this time. In random order they are:

A near-symmetrical shot of The Stern of the SS Great Britain at Bristol by Jayembee69:

We had four runners-up this time. In random order they are:

A near-symmetrical shot of The Stern of the SS Great Britain at Bristol by Jayembee69:

This picture makes it very clear how ship design has often tried to imitate fashionable architectural details. The SS Great Britain was the largest ship in the world when it was launched and something of the grandeur comes through even in a detail shot like this one.

Next up, Standing Guard by m oleathlobhair.

What I like about this picture is that is very organic: at first glance it could (almost) be a gnarled old face of a boulder in a field, left stranded by some geological process. But the inclusion of the second stone to the right disabuses the viewer of any such suspicion. The angle of the clouds and blue streak of sky remind me of the time-lapse shots of scudding clouds in films.

Next we have The Albert Memorial by richardr.

Richard's photo captures the excess of the memorial: not just gold and marble but mosaics and inlaid jewels. I must admit that until looking up the monument on Wikipedia I hadn't realised what an elaborate allegorical scheme it has. In Richard's photo I think we can see the 'Agriculture' group and the 'Engineering' group of marble sculptures. I will certainly look more carefully at the monument next time I am in Kensington.

Richard's photo captures the excess of the memorial: not just gold and marble but mosaics and inlaid jewels. I must admit that until looking up the monument on Wikipedia I hadn't realised what an elaborate allegorical scheme it has. In Richard's photo I think we can see the 'Agriculture' group and the 'Engineering' group of marble sculptures. I will certainly look more carefully at the monument next time I am in Kensington.

The last of our runners-up is Southwell Minster by the-frantic-photographer.

I have fond memories of visiting Southwell Minster on a cathedrals tour about 10 years ago (that was in my wild youth, when anything seemed possible). It is a quiet place and the persistent foliage theme in the decoration - for example in the beautiful chapter house - fits the setting nicely. This close-up picture by the-frantic-photographer shows a honeycomb-like door from which the quatrefoil motif emerges as soon as you look at it carefully. This is the kind of close-up picture that I always try to take but always end up with disappointing results, but here we have a good example of how it can be done.

That crazy cathedrals road trip that my partner and I took ended at Lincoln and, coincidentally, this month's winner is a picture of Lincoln Cathedral by uplandswolf:

Many of you will know that the cathedral is at the top of a steep hill, and here we get a tremendous sense of the way in which the building seem to be reaching up even higher. The exuberance of all this stonework is heightened by the choice of the gothic arch through which to frame the main subject. Congratulations to uplandswolf for winning with a very different photograph from his Derelict signal box in March.

Wednesday, 18 September 2013

Andrew Minting on RCHME, Salisbury

In the latest in our series of posts on the RCHME series, we have a guest post by Andrew Minting, conservation officer in Salisbury, about the importance of the Salibury volume. Andrew writes:

If there’s one source of information I commend to those researching the buildings of the city of Salisbury, it’s the Royal Commission’s volume on the historic monuments outside of the cathedral close.

Its recent online publication is excellent news and makes the information much more readily accessible to the general public. The copy on my desk is well worn from use on a near-daily basis for many years, providing an understanding of individual buildings and the development of the city from its foundation. As an historical record of the city in the mid twentieth century, it is invaluable, including buildings that had been demolished from the 1950s onwards. In comparison with modern mapping, one can trace some of the dramatic redevelopments and losses of the last half-century – the extensive demolition to facilitate the ring road, the Old George and Cross Keys shopping malls, for example. Many buildings are brought to life through excellent detailed drawings of their timber frames, such as the Plume of Feathers, while plans showing chronological development are particularly useful for those considering the sensitivity of sites to proposed alterations.

The introduction and footnotes provide very useful pointers to all of other primary and secondary sources available, many of which are now to be found at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre.

One important note for those unfamiliar with the hardback version of the volume, the planned grid layout of much of the city centre led to the adoption of names for the blocks of the grid, known as chequers, in addition to street names. Where appropriate, the Royal Commission organised the monuments of the volume by chequer, rather than following the lengths of individual streets. Perhaps the most useful image for users of the online version is to be found in Plan 1, which shows both chequer and streetnames, although the Naish plan of 1716 is a beautiful alternative.

Andrew Minting

If there’s one source of information I commend to those researching the buildings of the city of Salisbury, it’s the Royal Commission’s volume on the historic monuments outside of the cathedral close.

Its recent online publication is excellent news and makes the information much more readily accessible to the general public. The copy on my desk is well worn from use on a near-daily basis for many years, providing an understanding of individual buildings and the development of the city from its foundation. As an historical record of the city in the mid twentieth century, it is invaluable, including buildings that had been demolished from the 1950s onwards. In comparison with modern mapping, one can trace some of the dramatic redevelopments and losses of the last half-century – the extensive demolition to facilitate the ring road, the Old George and Cross Keys shopping malls, for example. Many buildings are brought to life through excellent detailed drawings of their timber frames, such as the Plume of Feathers, while plans showing chronological development are particularly useful for those considering the sensitivity of sites to proposed alterations.

The introduction and footnotes provide very useful pointers to all of other primary and secondary sources available, many of which are now to be found at the Wiltshire and Swindon History Centre.

One important note for those unfamiliar with the hardback version of the volume, the planned grid layout of much of the city centre led to the adoption of names for the blocks of the grid, known as chequers, in addition to street names. Where appropriate, the Royal Commission organised the monuments of the volume by chequer, rather than following the lengths of individual streets. Perhaps the most useful image for users of the online version is to be found in Plan 1, which shows both chequer and streetnames, although the Naish plan of 1716 is a beautiful alternative.

Andrew Minting

Friday, 6 September 2013

July photo competition

Here are the results of our photo competition for July are now in. We have two runners-up this month, and they are (as ever) in no particular order:

Exeter Cathedral by richardr:

This Exeter angel strikes me as a melancholy one. Presumably leaning back in awe and admiration, in this photograph the angel seems rather to be going through some moment of existential angst - an impression given, I think, by the strong contrast in light and the cool tone of the stone.

Our second runner-up is, like richardr, a veteran of our BHO photo competition, uplandswolf. His Burghley House 2 has a sunnier palette:

Burghley House, in Lincolnshire, was the seat of the Cecils, secretaries of state who were powerful advisors to Elizabeth I and James I. The connection may not have been in uplandswolf's mind, but we have made the complete series of the calendar of the Cecil papers freely available on British History Online, for those who'd like to know more about their affairs of state.

Our winner for July depicts a less grand dwelling. Scotland 2013 by rachaellazenby shows part of Inchcolm Abbey on Inchcolm, one of the islands on the Firth of Forth:

The judges loved the light in this photograph, which lends the austere and rugged stonework grace and warmth.

Our thanks go to these three contributors, and all the other people who have included their photographs in the British History Online group. Please do keep adding your pictures.

Exeter Cathedral by richardr:

This Exeter angel strikes me as a melancholy one. Presumably leaning back in awe and admiration, in this photograph the angel seems rather to be going through some moment of existential angst - an impression given, I think, by the strong contrast in light and the cool tone of the stone.

Our second runner-up is, like richardr, a veteran of our BHO photo competition, uplandswolf. His Burghley House 2 has a sunnier palette:

Burghley House, in Lincolnshire, was the seat of the Cecils, secretaries of state who were powerful advisors to Elizabeth I and James I. The connection may not have been in uplandswolf's mind, but we have made the complete series of the calendar of the Cecil papers freely available on British History Online, for those who'd like to know more about their affairs of state.

Our winner for July depicts a less grand dwelling. Scotland 2013 by rachaellazenby shows part of Inchcolm Abbey on Inchcolm, one of the islands on the Firth of Forth:

The judges loved the light in this photograph, which lends the austere and rugged stonework grace and warmth.

Our thanks go to these three contributors, and all the other people who have included their photographs in the British History Online group. Please do keep adding your pictures.

Wednesday, 14 August 2013

Sarah Rose on Westmorland

In another in our series of posts by experts in particular counties, Dr Sarah Rose of Lancaster University writes for us about the RCHME volume for Westmorland:

I would like to reiterate the comments made by Professor Dyer, written in response to the online publication of the RCHME’s Northamptonshire volumes, regarding the general importance of this series. The number of architectural features included in these volumes, dating from the prehistoric era to the 18th century, together with the sheer breadth of research conducted by the Royal Commission, make them an essential starting point for anyone interested in landscape and place, whether they be actively engaged in research or merely curious.

Since its publication in 1936, the importance of the Westmorland volume has perhaps been underscored by the absence, to date, of a VCH volume for the county. As such, RCHME Westmorland has become a vital source for those writing in-depth local studies to county-wide surveys, including Matthew Hyde’s revised volume of Pevsner’s gazetteer for the ancient counties that make-up Cumbria.(1) The RCHME volume for Westmorland is particularly important as a pioneering survey of the county’s vernacular architecture, highlighting, for example, the rich legacy of plasterwork in traditional buildings:

Cumbria’s past is currently being explored in great detail by volunteer researchers working for the Victoria County History of Cumbria project, now in its third year. The RCHME volumes are cited at a national level as an essential resource for VCH researchers. This is as true for the volunteers working on Westmorland as in any other county. The RCHME volume often serves as an initial guide to the history of major local buildings, such as the parish church, for example, but also outlines important historical features which may be less obvious to the untrained eye.

In rural areas like Cumbria, an online version of RCHME for Westmorland tackles the issue of accessibility to resources of its kind, which are invariably limited to reference libraries and archives. For VCH volunteers, many who do not live in easy distance of such facilities, this online publication should be particularly welcome.

(1) M. Hyde and N. Pevsner, Cumbria: Cumberland, Westmorland and Furness. The Buildings of England (London, 2010).

I would like to reiterate the comments made by Professor Dyer, written in response to the online publication of the RCHME’s Northamptonshire volumes, regarding the general importance of this series. The number of architectural features included in these volumes, dating from the prehistoric era to the 18th century, together with the sheer breadth of research conducted by the Royal Commission, make them an essential starting point for anyone interested in landscape and place, whether they be actively engaged in research or merely curious.

Since its publication in 1936, the importance of the Westmorland volume has perhaps been underscored by the absence, to date, of a VCH volume for the county. As such, RCHME Westmorland has become a vital source for those writing in-depth local studies to county-wide surveys, including Matthew Hyde’s revised volume of Pevsner’s gazetteer for the ancient counties that make-up Cumbria.(1) The RCHME volume for Westmorland is particularly important as a pioneering survey of the county’s vernacular architecture, highlighting, for example, the rich legacy of plasterwork in traditional buildings:

Cumbria’s past is currently being explored in great detail by volunteer researchers working for the Victoria County History of Cumbria project, now in its third year. The RCHME volumes are cited at a national level as an essential resource for VCH researchers. This is as true for the volunteers working on Westmorland as in any other county. The RCHME volume often serves as an initial guide to the history of major local buildings, such as the parish church, for example, but also outlines important historical features which may be less obvious to the untrained eye.

In rural areas like Cumbria, an online version of RCHME for Westmorland tackles the issue of accessibility to resources of its kind, which are invariably limited to reference libraries and archives. For VCH volunteers, many who do not live in easy distance of such facilities, this online publication should be particularly welcome.

(1) M. Hyde and N. Pevsner, Cumbria: Cumberland, Westmorland and Furness. The Buildings of England (London, 2010).

Wednesday, 31 July 2013

June photo competition

Somewhat delayed by the advent of summer holidays, here are the results of the BHO photo competition for June.

We had two runners-up, in no particular order. The first was this beautifully composed shot of the ceiling of Peterborough Cathedral by Richardr:

The shot makes clear the love of geometry and celestial order in the medieval builders and patrons of the cathedral. This is even clearer in the full-size photo on Flickr. Ecclesiastical ceilings were often treated as a typological form of the sky; some also had a blue ground for gold stars, as in St Mary's Church in Beverley. Kepler was lead astray in his astronomical theories by his desire to equate the planets and their relationships with the five Platonic Solids. And today, of course, we still impose our ideas of order on the cosmos: what we see as constellations are stars that have no necessary relation to each other whatsoever.

Our other runner-up was Chepstow & Monmouth 018 by expat a. I think here we can see the comedic side of the medieval mind. The devil and the smiling head seem to be to be moving towards each other in an almost cartoonish way; it's hard to be sure but I suspect that the face on the right expresses a complacent unawareness of the wages of sin. Although some saints are credited with remaining calm in the face of the devil.

Our winner this month is another ceiling, that of The New Room:

You probably recognise the photographer as the same as Peterborough Cathedral above, Richardr. Although we didn't plan it this way, it does provide an instructive contrast in ecclesiastical ceilings. The New Room in Bristol claims to be the oldest Methodist building in the world.

I wonder if we should resist the temptation to see the different style of the ceiling here as due to a nonconformist simplicity. After all, this building of 1739 has stylistic affinities with Anglican churches of the period (white walls, clear glass) such as the wonderful Hawksmoor churches built a decade or two earlier under the Fifty New Churches Act.

However, when I first saw this picture it put me most in mind of the ceiling of Wren's Octagon Room at the Royal Observatory. This room was used by the first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, who worked here compiling his meticulous stellar catalogue.

We had two runners-up, in no particular order. The first was this beautifully composed shot of the ceiling of Peterborough Cathedral by Richardr:

The shot makes clear the love of geometry and celestial order in the medieval builders and patrons of the cathedral. This is even clearer in the full-size photo on Flickr. Ecclesiastical ceilings were often treated as a typological form of the sky; some also had a blue ground for gold stars, as in St Mary's Church in Beverley. Kepler was lead astray in his astronomical theories by his desire to equate the planets and their relationships with the five Platonic Solids. And today, of course, we still impose our ideas of order on the cosmos: what we see as constellations are stars that have no necessary relation to each other whatsoever.

Our other runner-up was Chepstow & Monmouth 018 by expat a. I think here we can see the comedic side of the medieval mind. The devil and the smiling head seem to be to be moving towards each other in an almost cartoonish way; it's hard to be sure but I suspect that the face on the right expresses a complacent unawareness of the wages of sin. Although some saints are credited with remaining calm in the face of the devil.

Our winner this month is another ceiling, that of The New Room:

You probably recognise the photographer as the same as Peterborough Cathedral above, Richardr. Although we didn't plan it this way, it does provide an instructive contrast in ecclesiastical ceilings. The New Room in Bristol claims to be the oldest Methodist building in the world.

I wonder if we should resist the temptation to see the different style of the ceiling here as due to a nonconformist simplicity. After all, this building of 1739 has stylistic affinities with Anglican churches of the period (white walls, clear glass) such as the wonderful Hawksmoor churches built a decade or two earlier under the Fifty New Churches Act.

However, when I first saw this picture it put me most in mind of the ceiling of Wren's Octagon Room at the Royal Observatory. This room was used by the first Astronomer Royal, John Flamsteed, who worked here compiling his meticulous stellar catalogue.

Thursday, 18 July 2013

Peter Salt on RCHME, Cambridgeshire

We're pleased to announce that all volumes of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England are now published on British History Online.

Of the last volumes published, three related to Cambridgeshire. Our own Cambridgeshire man, Peter Salt, Editor of the Bibliography of British and Irish History, kindly agreed to write a blog post about the City of Cambridge volume. Peter writes:

Of the last volumes published, three related to Cambridgeshire. Our own Cambridgeshire man, Peter Salt, Editor of the Bibliography of British and Irish History, kindly agreed to write a blog post about the City of Cambridge volume. Peter writes:

When the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments' inventory

of the city of Cambridge was published in 1959 in two substantial volumes with

a separate container of plans,1 they were priced at the princely sum of five guineas (£5.25). They were out of print by the time that I

paid £52.00 for my copy about 25 years later.

I was conscious at the time that this was virtually ten times the

original selling price but I reasoned to myself that they would never be

cheaper. So I greet the appearance of

the Cambridge inventory in British History Online with mixed feelings - freely

accessible online publication, to the high standards associated with British

History Online, is a great boon to scholarship but may reduce demand for the printed

volumes and therefore may have devalued my copy!

Naturally, College and University buildings fill most of the

Cambridge inventory. However, it also

covers the growth of the town.

Furthermore, from 1946 the Commissioners were empowered not only to make

an inventory of 'Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions' predating

the eighteenth century, as had been done before World War II, but also to

describe 'such further Monuments and Constructions subsequent to' 1714 'as may

seem in your discretion to be worthy of mention'.2 In the Cambridge inventory, as in the preceding

one covering Dorset, this resulted in the adoption of an 1850 cut-off date3

and, for buildings that could be identified as being earlier than 1850, little

or no selection seems to have been applied in practice. Furthermore, as the preface observed, 'the

first half of the 19th century' was 'a period of notable urban development in

Cambridge'.4 The result was that the volumes cover not

only internationally known monuments such as King's College Chapel, but also

include some quite modest terraced houses - so modest, indeed, as to include

the house in which I lived from 1991 to 2005, which had been built (it was

suggested) for the "outside staff" of the larger houses in the same

development.5

Such houses were sometimes recorded with almost as much care as the major monuments - the development of which my house formed a part is illustrated by a layout diagram and by internal plans of representative houses, the latter presented alongside plans of similar houses to facilitate comparison. Even so, there were times when the surveyors were virtually unable to find anything to say: after they had diplomatically described early nineteenth-century houses in Brunswick Walk as 'pleasant in their simplicity and lack of ostentation', they were reduced to reporting that 'Willow Place and Causeway Passage ... are even less distinguished than the foregoing'.6 Nonetheless, the recording and comparison of small terraced houses that were then little more than one hundred years old would have been ground-breaking at the time.

Such houses were sometimes recorded with almost as much care as the major monuments - the development of which my house formed a part is illustrated by a layout diagram and by internal plans of representative houses, the latter presented alongside plans of similar houses to facilitate comparison. Even so, there were times when the surveyors were virtually unable to find anything to say: after they had diplomatically described early nineteenth-century houses in Brunswick Walk as 'pleasant in their simplicity and lack of ostentation', they were reduced to reporting that 'Willow Place and Causeway Passage ... are even less distinguished than the foregoing'.6 Nonetheless, the recording and comparison of small terraced houses that were then little more than one hundred years old would have been ground-breaking at the time.

In some cases the survey recorded buildings that were soon

to be demolished. Indeed, Willow Place

and Causeway Passage have largely vanished.

That small late-Georgian terraced houses should fall victim to 1960s and

1970s improvements is not surprising (they had been assessed

in 1950 as "fourth class" and although, if they had lasted a few

years longer, they might well have been refurbished and extended as desirable pieds

à

terre, it has to be said that our favourable view of Georgian domestic

architecture rests in part on the destruction of its meanest specimens). Perhaps more surprising in a town that trades

on its "heritage" is the loss of the 'good brick front of 1727'

belonging to the Central

Hotel on Peas Hill, where Pepys was supposed to have 'drank pretty hard' in

1660, and one of the secular buildings deemed by the Commissioners to be

'especially worthy of preservation',7 but replaced in 1960-2 by a hostel

for King's College.

As Professor Chris Dyer observed in his post

in this blog on the Northamptonshire volumes, the Royal Commission's

post-war inventory volumes 'marked a high point' in its

work that was not sustained. Since

1984 the Commission and English Heritage (into which the Commission was

incorporated in 1999) have continued to record and to analyze, but have

published the results in thematic volumes, rather than in parish by parish (or

town by town) inventories. The foreword to the last inventory volume, published in 1984, admitted

that 'the creation of an adequately researched and assessed inventory of

England's archaeological and architectural heritage is now accepted ... as a

complex and infinite task' (my

emphasis). Indeed, what seems 'adequately

researched and assessed' to one generation may disappoint the next one. Now that Causeway Passage has vanished from

the map we might well wish that the inventory had gone into a bit more

detail. And, just as 1714 came to seem,

after World War II, too remote an end date for the survey, resulting in an

expansion of the Commissioners' remit, the 1850 cut off chosen for the

Cambridge volumes will seem too remote to those who want to study Cambridge's

later nineteenth-century growth. In

practice, though, we must be grateful for what was achieved, and (notwithstanding

the potential decline in the value of my printed copy) the online publication

of the inventories is very much to be welcomed.

1 All footnote references are to the city of Cambridge

inventory. The volumes were continuously

paginated and are treated as a single entity by British History Online.

7 Monument 146, included in the list of buildings especially worthy of preservation at p. xxx

Wednesday, 26 June 2013

May photo competition

It's time to let you know our shortlist for the BHO photography competition in May.

This month there was a shortlist of three for the judges to ponder and argue over. Eventually we chose a winner, but the two runners-up (in no particular order) were Castle Rising, by wazman27:

The judges thought that the framing of the picture, through the gateway, was very effective in this photograph. The sense of menace, or at least authority, perhaps conveys what the castle's builders wanted to achieve in those who approached it.

Our other runner-up is rather different in tone, the Peterborough Lido by uplandswolf (who has featured several times in this blog before!):

Looking again at this photo just now, a colleague remarked upon the almost Palladian classicism of the structure. The foreground gardens also have a rather formal feel. None of this seems to detract from the festive tone of the photograph.

Our winner is not quite so festive, the Ossuary at St Leonard's Church in Hythe, by Alan Denney:

Congratulations to Alan for this powerful picture, which will be reminding us our mortality for the next month on the BHO homepage. Few ossuaries have survived in England and, as one of the judges remarked, "it reminds us that local history isn't just about buildings, but also about the people who lived in or built them".

Please do keep your photos coming to the BHO group. We've been very much enjoying looking through them.

This month there was a shortlist of three for the judges to ponder and argue over. Eventually we chose a winner, but the two runners-up (in no particular order) were Castle Rising, by wazman27:

The judges thought that the framing of the picture, through the gateway, was very effective in this photograph. The sense of menace, or at least authority, perhaps conveys what the castle's builders wanted to achieve in those who approached it.

Our other runner-up is rather different in tone, the Peterborough Lido by uplandswolf (who has featured several times in this blog before!):

Looking again at this photo just now, a colleague remarked upon the almost Palladian classicism of the structure. The foreground gardens also have a rather formal feel. None of this seems to detract from the festive tone of the photograph.

Our winner is not quite so festive, the Ossuary at St Leonard's Church in Hythe, by Alan Denney:

Congratulations to Alan for this powerful picture, which will be reminding us our mortality for the next month on the BHO homepage. Few ossuaries have survived in England and, as one of the judges remarked, "it reminds us that local history isn't just about buildings, but also about the people who lived in or built them".

Please do keep your photos coming to the BHO group. We've been very much enjoying looking through them.

Monday, 10 June 2013

Chris Dyer on RCHME, Northants

British History Online recently published the six inventory volumes for the county of Northamptonshire. To help to put these volumes in context, Professor Chris Dyer has kindly written a guest blog post explaining their importance. Chris Dyer is Emeritus Professor of Local and Regional History at the University of Leicester, and so is the perfect person to introduce these volumes. Professor Dyer writes:

"The inclusion of the Northamptonshire volumes of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, England on British History Online will be welcomed by anyone interested in Northamptonshire, but also in the study of many aspects of the material evidence for the history of the English countryside. When they appeared these volumes marked a high point in the work of the Royal Commission. There were volumes on historic buildings, which was the traditional strength of the RCHME's earlier county inventories, but these were more inclusive and systematic than in the early volumes, because village plans were included, with the older buildings marked, and accompanied by brief descriptions of ordinary houses and cottages, and occasional plans and photographs. Larger houses and churches, the usual subjects of surveys of local architecture, received full treatment as well. All of this was thoroughly researched, with documentary background studies as well as scholarly architectural analyses.

The great innovation and achievement of the Northamptonshire volumes however, is to be observed in the volumes devoted to archaeological sites. Air photograph evidence of field boundaries and settlement sites, mainly of the iron age and Romano-British period, were transcribed on to modern maps, and for the medieval period hundreds of sites marked by earthworks were carefully planned and analysed. They included the famous deserted medieval village sites, and the remains of villages that still survived but had once been much larger. These had only been identified as sites 30 years or so before the Royal Commission planned them. Part of the medieval rural landscape were the fields, visible as ridge and forrow, and some examples of these survivals were also planned. There was also a great variety of sites and features : park boundaries, moated sites, fishponds, pillow mounds from former rabbit warrens, sites of water mills and the mounds on which windmills had stood. Any past activity which involved digging into the earth and making heaps left indelible traces for the researchers of the RCHME to discover. As the work progressed the plans grew ever more sophisticated, and the interpretations of the meaning of the sites became more accomplished. To give one example of the lessons learned from preparing these volumes, post medieval garden earthworks were recognized and planned in detail, and researchers all over the country realised that the expanses of mounds and ditches that had puzzled them suddenly became explicable. Anyone interested in the formation and decline of rural settlement, landscape history, and aristocratic manipulations of the landscape will find important source material in these volumes. They also mark a chapter in the intellectual history of the study of the rural past. They are finally a sad comment on the philistine treatment of the heritage, because not long after these volumes were completed, instead of declaring the intention of carrying out similar studies of the other English counties, the Royal Commission was merged with English Heritage, and ceased to compile inventories."

Chris Dyer

"The inclusion of the Northamptonshire volumes of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments, England on British History Online will be welcomed by anyone interested in Northamptonshire, but also in the study of many aspects of the material evidence for the history of the English countryside. When they appeared these volumes marked a high point in the work of the Royal Commission. There were volumes on historic buildings, which was the traditional strength of the RCHME's earlier county inventories, but these were more inclusive and systematic than in the early volumes, because village plans were included, with the older buildings marked, and accompanied by brief descriptions of ordinary houses and cottages, and occasional plans and photographs. Larger houses and churches, the usual subjects of surveys of local architecture, received full treatment as well. All of this was thoroughly researched, with documentary background studies as well as scholarly architectural analyses.

The great innovation and achievement of the Northamptonshire volumes however, is to be observed in the volumes devoted to archaeological sites. Air photograph evidence of field boundaries and settlement sites, mainly of the iron age and Romano-British period, were transcribed on to modern maps, and for the medieval period hundreds of sites marked by earthworks were carefully planned and analysed. They included the famous deserted medieval village sites, and the remains of villages that still survived but had once been much larger. These had only been identified as sites 30 years or so before the Royal Commission planned them. Part of the medieval rural landscape were the fields, visible as ridge and forrow, and some examples of these survivals were also planned. There was also a great variety of sites and features : park boundaries, moated sites, fishponds, pillow mounds from former rabbit warrens, sites of water mills and the mounds on which windmills had stood. Any past activity which involved digging into the earth and making heaps left indelible traces for the researchers of the RCHME to discover. As the work progressed the plans grew ever more sophisticated, and the interpretations of the meaning of the sites became more accomplished. To give one example of the lessons learned from preparing these volumes, post medieval garden earthworks were recognized and planned in detail, and researchers all over the country realised that the expanses of mounds and ditches that had puzzled them suddenly became explicable. Anyone interested in the formation and decline of rural settlement, landscape history, and aristocratic manipulations of the landscape will find important source material in these volumes. They also mark a chapter in the intellectual history of the study of the rural past. They are finally a sad comment on the philistine treatment of the heritage, because not long after these volumes were completed, instead of declaring the intention of carrying out similar studies of the other English counties, the Royal Commission was merged with English Heritage, and ceased to compile inventories."

Chris Dyer

Wednesday, 29 May 2013

Roman Inscriptions in the RCHME

Over the last couple of months we have published two volumes about Roman remains in England: Roman London and Eburacum, Roman York. These have been part of our current digitisation of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments inventory series for England.

This subject matter is somewhat unusual for British History Online, although we do have similar material elsewhere, as in the Victoria County History volume for Oxfordshire, Volume 1, and as part of the RCHME we will soon be adding a volume on Iron Age and Romano-British monuments in the Cotswolds. But these two latest RCHME volumes have been a bit of a challenge to digitise because of the large number of inscriptions they contain.

Roman writing did not contain such useful things as spaces between letters, punctuation or differences of case. If you owned a book yourself then you could mark it up for reading yourself, to make things easier. Obviously this couldn't be done with inscriptions, so there was a tendency to add some former of marker between words to make things easier for the reader; here it is done with a mid dot in a dedication tablet from York:

Elsewhere in Roman inscriptions covered by the RCHME a leaf or other symbol is used. Notice that this still doesn't make the inscription very easy to read: words can spill over onto the next line without any indication that they are doing so, as in the name HIERONYMIANVS above; also, like text messages today, Roman inscriptions tend to be highly abbreviated. Fortunately the RCHME editors have painstakingly transcribed, and then translated, the inscriptions for us, with abbreviations expanded. Here is the above:

DEO ▵ SANCTO

SERAPI

TEMPLVM ▵ A SO

LO FECIT

CL(AVDIVS) ▵ HIERONY

MIANVS ▵ LEG(ATVS)

LEG(IONIS) ▵ VI ▵ VIC(TRICIS)

'To the holy god Serapis, Claudius Hieronymianus, legate of the Sixth Legion Victorious, built this temple from the ground.'

The editors then give us quite a lot of information about who this Claudius Hieronymianus was:

"Claudius Hieronymianus is identified (Prosopographia Imperii Romani, 2nd ed., II, 206, no. 888) with a vir clarissimus of this name involved in a judgment by Papinian about a will (Ulpian, Digest, 33, 7, 12, 40) and with the praeses of Cappadocia whom Tertullian (ad Scap. 3) mentions at the turn of the 2nd and 3rd centuries as persecuting Christians after his wife's conversion..."

Thanks to the efforts of the RCHME editors for these volumes, there is a wealth of information of this type - photographs, transcriptions and translations - now available to all.

This subject matter is somewhat unusual for British History Online, although we do have similar material elsewhere, as in the Victoria County History volume for Oxfordshire, Volume 1, and as part of the RCHME we will soon be adding a volume on Iron Age and Romano-British monuments in the Cotswolds. But these two latest RCHME volumes have been a bit of a challenge to digitise because of the large number of inscriptions they contain.

Roman writing did not contain such useful things as spaces between letters, punctuation or differences of case. If you owned a book yourself then you could mark it up for reading yourself, to make things easier. Obviously this couldn't be done with inscriptions, so there was a tendency to add some former of marker between words to make things easier for the reader; here it is done with a mid dot in a dedication tablet from York:

Elsewhere in Roman inscriptions covered by the RCHME a leaf or other symbol is used. Notice that this still doesn't make the inscription very easy to read: words can spill over onto the next line without any indication that they are doing so, as in the name HIERONYMIANVS above; also, like text messages today, Roman inscriptions tend to be highly abbreviated. Fortunately the RCHME editors have painstakingly transcribed, and then translated, the inscriptions for us, with abbreviations expanded. Here is the above:

DEO ▵ SANCTO

SERAPI

TEMPLVM ▵ A SO

LO FECIT

CL(AVDIVS) ▵ HIERONY

MIANVS ▵ LEG(ATVS)

LEG(IONIS) ▵ VI ▵ VIC(TRICIS)

'To the holy god Serapis, Claudius Hieronymianus, legate of the Sixth Legion Victorious, built this temple from the ground.'

The editors then give us quite a lot of information about who this Claudius Hieronymianus was:

"Claudius Hieronymianus is identified (Prosopographia Imperii Romani, 2nd ed., II, 206, no. 888) with a vir clarissimus of this name involved in a judgment by Papinian about a will (Ulpian, Digest, 33, 7, 12, 40) and with the praeses of Cappadocia whom Tertullian (ad Scap. 3) mentions at the turn of the 2nd and 3rd centuries as persecuting Christians after his wife's conversion..."

Thanks to the efforts of the RCHME editors for these volumes, there is a wealth of information of this type - photographs, transcriptions and translations - now available to all.

Monday, 20 May 2013

April photo competition winner

For this month's competition the voting among my colleagues gave us a shortlist of three. In no particular order the two runners-up were:

Tudor Barlow's picture of the cloisters at Gloucester Cathedral

This will be a familiar setting to many but the light in this photograph is evocative. The bright light of the open doorway at the end of the cloisters conveys just the numinous effect that Gothic architecture, presumably, aspires to achieve.

Our other runner up was Disused Slate Mine by stephen bolton1. A photo which I find gritty and melancholy but also eerie - or, if you like, earthy and unearthly at the same time.

After discussion, however, we chose as our winner, Little Moreton Hall by alan tunnicliffe

Like Gloucester Cathedral, this a well known setting, but the photograph is quite unsentimental, perhaps because of the tripartite sky: part lowering, part blue and part irradiated. The context of the house seems to be in harmony with the building, both being somewhat overgrown and chaotic.

Everyone is welcome to add their photos the the British History Online group on Flickr. We are picking our favourite every month in order to celebrate our 10th anniversary. The winning photo will, with permission, appear on the BHO homepage.

Tudor Barlow's picture of the cloisters at Gloucester Cathedral

This will be a familiar setting to many but the light in this photograph is evocative. The bright light of the open doorway at the end of the cloisters conveys just the numinous effect that Gothic architecture, presumably, aspires to achieve.

Our other runner up was Disused Slate Mine by stephen bolton1. A photo which I find gritty and melancholy but also eerie - or, if you like, earthy and unearthly at the same time.

After discussion, however, we chose as our winner, Little Moreton Hall by alan tunnicliffe

Like Gloucester Cathedral, this a well known setting, but the photograph is quite unsentimental, perhaps because of the tripartite sky: part lowering, part blue and part irradiated. The context of the house seems to be in harmony with the building, both being somewhat overgrown and chaotic.

Everyone is welcome to add their photos the the British History Online group on Flickr. We are picking our favourite every month in order to celebrate our 10th anniversary. The winning photo will, with permission, appear on the BHO homepage.

Thursday, 25 April 2013

March photo competition winner

Our photo competition is ongoing through the summer, when we will be celebrating British History Online's 10th anniversary. As with last month, a great variety of images were added our BHO Flickr group.

This month we shortlisted three, not because the quality of the others was low but because of the way the voting broke down (staff of IHR Digital vote for their favourites, which then produces a cut-off point for the shortlist). Members of the BHO Working Group then met to discuss the shortlist and choose a final winner.

Again, the shortlisted photographers have kindly sent us copies of their photographs and permission to post them here.

Our two runners-up, in no particular order, were joycemacadam's Scotney Castle LR:

The judges admired the composition of this photograph, with the inclusion of quite a lot of surroundings giving pertinent information about the building's context.

Secondly we have Bewcastle Ancient Cross by karenwithak:

This was an interesting picture, the ancient cross somewhat out of place among the more conventional gravestones, and yet expressing the same commemorative purpose.

After much discussion, we chose as April's winner Derelict signal box in Stamford, by uplandswolf.

Derelict signal box will appear on the BHO homepage gallery for a month.

Keen readers of this blog may remember that uplandswolf was a runner-up in last month's competition, so congratulations again to him. The judges like the unusual and dilapidated subject, a timely reminder of our industrial heritage, alongside the just-visible modern railways station. It turns out that there is an online database of signal boxes, from which you can find that, for example, the Stamford example was built in 1893.

This month we shortlisted three, not because the quality of the others was low but because of the way the voting broke down (staff of IHR Digital vote for their favourites, which then produces a cut-off point for the shortlist). Members of the BHO Working Group then met to discuss the shortlist and choose a final winner.

Again, the shortlisted photographers have kindly sent us copies of their photographs and permission to post them here.

Our two runners-up, in no particular order, were joycemacadam's Scotney Castle LR:

The judges admired the composition of this photograph, with the inclusion of quite a lot of surroundings giving pertinent information about the building's context.

Secondly we have Bewcastle Ancient Cross by karenwithak:

This was an interesting picture, the ancient cross somewhat out of place among the more conventional gravestones, and yet expressing the same commemorative purpose.

After much discussion, we chose as April's winner Derelict signal box in Stamford, by uplandswolf.

Derelict signal box will appear on the BHO homepage gallery for a month.

Keen readers of this blog may remember that uplandswolf was a runner-up in last month's competition, so congratulations again to him. The judges like the unusual and dilapidated subject, a timely reminder of our industrial heritage, alongside the just-visible modern railways station. It turns out that there is an online database of signal boxes, from which you can find that, for example, the Stamford example was built in 1893.

Thursday, 21 March 2013

Image Copyright: An Introduction (2)

Our Permissions Controller for the digitisation of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England, Rachael Lazenby, has written an introductory guide to copyright for images, drawing on her experience on this project and on other work that she has done. Part one of Rachael's guide appeared here; the rest of the guide is below.

(5)

(5)

(1) This link will redirect to information on the European memorandum of understanding on orphan works http://www.ifrro.org/content/i2010-digital-libraries retrieved on 22/2/2013.

(2) http://www.copyrightservice.co.uk/copyright/p01_uk_copyright_law retrieved on 22/2/2013

(3) The difficulties of dealing with such issues are discussed in these articles on policing the internet: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-17111041 retrieved on 22/2/2013

(5) St Swithin’s Church London Stone. This is a Wren church destroyed in the Blitz and not restored.

Copyright and images - an introductory guide, part 2

Rachael Lazenby

Identifying copyright holders, orphan works and due diligence

Frequently

publishers will include images which have appeared in other

publications. The modern convention is to include a caption with the

image which makes it very clear who the copyright holder is and who

should be approached for permission to reproduce an image. However, the

older the publication, the more likely it is that such information will

not be found in a caption. The RCHME volumes, the earliest of which date

from 1913, contained copyright holder information in a variety of

places. This included the illustration lists, footnotes, and the

preliminary materials of the texts as well as in illustration captions.

When considering using images from older works it is advisable to check

in all these places for information on the copyright holder if the

original publisher no longer exists or does not retain rights

information on older publications. Internet searches, local history

societies and local museums may also be able to help in establishing the

copyright status of historical images.

Inevitably

there were some images included in the original RCHME volumes whose

owners could not be traced. Such images are known as orphan works.

Different organisations take different stances on how to approach such

images and every organisation will have advice on what constitutes due

diligence in attempting to establish a copyright holder.(1) A record

should be kept of all efforts made in trying to trace the current rights

holder.

Crown Copyright

Crown

Copyright applies to images produced by certain UK government bodies

and lasts for 50 years. The National Archives has a very informative section on this topic, including a list of bodies whose images now fall

under Crown Copyright. Many

images which are protected by Crown Copyright can be used if a link

appears with the image directing the reader to a ‘click-to-use’ licence.

Fair use and Enforcement

So

far I’ve tried to avoid distinguishing between reproducing images for a

limited circulation (such as a dissertation) and a wide circulation

(such as a paper published in a journal). Theoretically copyright law

covers any reproduction of a work regardless of the circulation or the

commercial value of the work. Of course in practical terms the greater

the commercial value of an image the higher the likelihood that the

copyright holder may take legal action to prevent or punish any

unauthorised use of their image.

Fair

use is a concept which enables students and researchers to provide

examples and quotations of other people’s works in essays and papers

without first obtaining permission from the originator. Generally

speaking quotations tend to pose fewer problems than images and

providing they appear in the body of a text and for educational,

critical or journalistic purposes, they can be used without express

permission. Most educational institutions and publishers have a legal

team who will be able to advise on any concerns you may have about

reproducing images. In addition universities will often provide guidance

on matters of copyright in student handbooks.

It

is important to note that while fair use can be used as a legal

defence, copyright is a complex issue, and copyright holders have the

right to protect their work from any unauthorised use.(2) Following the

principles of fair use will not necessarily prevent a case from going to

court. The internet has made it easier to reproduce images without the

consent of the copyright holder and the laws covering copyright are

constantly evolving in response to new cases.(3) Although the copyright

of images of buildings belongs to the photographer or artist, an

interesting case went through the French courts a couple of years ago

concerning the Eiffel Tower. Photos of the tower at night were deemed to

be protected by copyright law as the lighting display constitutes a

work of art.(4)

I hope this post has shed some light on the issues surrounding copyright of images. A few key points to take away with you are:

- Copyright arises in a work, it does not have to be registered.

- Publicly accessible content is not necessarily in the public domain.

- Record your efforts to trace copyright holders if you intend on reproducing orphan works.

- Stay within the guidelines of ‘fair use’ but bear in mind it will not always prevent legal action.

- Check with your institution’s legal department if you have any doubts about content you intend to use.

(1) This link will redirect to information on the European memorandum of understanding on orphan works http://www.ifrro.org/content/i2010-digital-libraries retrieved on 22/2/2013.

(2) http://www.copyrightservice.co.uk/copyright/p01_uk_copyright_law retrieved on 22/2/2013

(3) The difficulties of dealing with such issues are discussed in these articles on policing the internet: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-17111041 retrieved on 22/2/2013

(5) St Swithin’s Church London Stone. This is a Wren church destroyed in the Blitz and not restored.

Tuesday, 12 March 2013

Our First Photo Winner

In January we launched a photo competition on Flickr to celebrate the 10-year anniversary of British History Online. Because we began mid-way through January, we decided to judge all of January and February's submissions together (there were nearly 200) and pick our first winner. We can't offer a prize, except that the winning photo will be displayed on the BHO homepage for a month, with credit and a link to the photograph on Flickr, of course.

Here I'm going to show the shortlisted photographs, whose owners have kindly sent us low-resolution versions and permission to post them here. Other photographs, which didn't make this shortlist, were also admired by the judges. Our thanks to everyone who entered.

The competition will be running again next month, so there is still time to enter if you'd like to. Simply post read the rules we've set out in the BHO Flickr group and add your photos.

First we'd like to give honourable mention to a photo which was entered by a staff member and so not eligible to win. Fade Away is by Alex Craven, who is the Assistant County Editor for the VCH, Wiltshire series; it shows the cloisters of Gloucester Cathedral:

There were five shortlisted photos. Our four runners-up, in no particular order, were:

The Palladian Bridge, in Prior Park, Bath, by shinytreats, a picture whose compositional balance seems in keeping with the style of its subject:

Then we have Normanton Church 4 by uplandswolf. The church as a focus of interest in its eerie landscape is emphasised by the people outside it:

You may not recognise this building from the unusual perspective, unless you are a cathedral roofs specialist. This is Norwich Cathedral: the Crossing by White Stilton - a striking and evocative image:

An urban perspective on historic buildings was provided by Mark Kirby5 in his photograph of St Vedast in the City of London. The judges admired the strong verticals in this picture:

That meant that our first winner was this unusual juxtaposition, in a photo of St Clement's Church, West Thurrock, by Whipper_snapper. Congratulations to Whipper_snapper, our first winner, and to our runners up.

You can see from the photos posted here what a difficult choice we had. Please do have a look at all the photos in the BHO group, and even add some more if you wish.

Here I'm going to show the shortlisted photographs, whose owners have kindly sent us low-resolution versions and permission to post them here. Other photographs, which didn't make this shortlist, were also admired by the judges. Our thanks to everyone who entered.

The competition will be running again next month, so there is still time to enter if you'd like to. Simply post read the rules we've set out in the BHO Flickr group and add your photos.

First we'd like to give honourable mention to a photo which was entered by a staff member and so not eligible to win. Fade Away is by Alex Craven, who is the Assistant County Editor for the VCH, Wiltshire series; it shows the cloisters of Gloucester Cathedral:

There were five shortlisted photos. Our four runners-up, in no particular order, were:

The Palladian Bridge, in Prior Park, Bath, by shinytreats, a picture whose compositional balance seems in keeping with the style of its subject:

Then we have Normanton Church 4 by uplandswolf. The church as a focus of interest in its eerie landscape is emphasised by the people outside it:

You may not recognise this building from the unusual perspective, unless you are a cathedral roofs specialist. This is Norwich Cathedral: the Crossing by White Stilton - a striking and evocative image:

An urban perspective on historic buildings was provided by Mark Kirby5 in his photograph of St Vedast in the City of London. The judges admired the strong verticals in this picture:

That meant that our first winner was this unusual juxtaposition, in a photo of St Clement's Church, West Thurrock, by Whipper_snapper. Congratulations to Whipper_snapper, our first winner, and to our runners up.

You can see from the photos posted here what a difficult choice we had. Please do have a look at all the photos in the BHO group, and even add some more if you wish.

Wednesday, 6 March 2013

Image Copyright: An Introduction (1)

Our Permissions Controller for the digitisation of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England, Rachael Lazenby, has written an introductory guide to copyright for images, drawing on her experience on this project and on other work that she has done. This is part one of Rachael's guide; the second part will follow shortly.

I’ve recently been working on the project to digitise the inventory volumes of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England (RCHME). Some of the volumes are already live and can be accessed here.

My role has been to identify all images which were not provided by the Commission and seek permission to reuse them on British History Online. A full report on the methodology I devised for this work along with the results is freely available and is published here.

The work has touched upon many issues relating to copyright which are common when using images in research and so I thought it would be useful to explain some of the basics of copyright, how it affects images in particular, along with providing links to various resources available online.

Definition of Copyright

Where better to start than with a definition of what copyright actually is:

A key feature of copyright is that it arises in a work the moment it is created by the originator. It does not have to be registered in the way that a patent might be for a process or a product. It is also important to note that ideas are not subject to copyright - it is the expression of ideas that is subject to copyright. This expression might be a photograph, a piece of text, a musical score or a painting. Copyright may be assigned by the originator to another party or waived by the copyright holder in certain circumstances.

Wherever an originator chooses to display or publish their work the copyright of the work remains with them unless they explicitly assign it to another party or until a fixed number of years have passed after their death. Copyright law varies country by country but in the UK a work remains in copyright until 70 years after the death of the creator at which point it passes into the public domain.

Misconceptions about the right to use images, especially those appearing online, abound. One of the most common is that if an image does not appear with the copyright symbol and a named copyright holder it is not protected by copyright law. Although such copyright notices can help identify a copyright holder, images without this symbol are still protected by copyright law. An image that is publicly accessible is still protected by copyright and an image being publicly accessible does not mean it is in the public domain. Copyright protects a work from any unauthorised use. Even if the reproduction of an image is not commercial, for example if it appears in a blog post, it is not legal without the permission of the originator.

Reproducing art and photographs

Cases involving paintings and drawings which are owned by museums can be complex. For example, should you wish to reproduce a photo of a painting by a living artist, you will have to gain permission from the artist, in addition to the permission of the organisation who owns the photo. It is frequently the case that photography is not permitted in museums and galleries, but if you have taken the photo yourself, and the composition is artistic and takes in more than just the painting itself, it may not be necessary to obtain permission. If an artist is deceased you may have to approach their estate for permission to reproduce an image if they have died within the last 70 years.

There are some organisations which specialise in sourcing paintings and drawings and for a fee will make available a high resolution scan of the work as well as arranging permission for an image to be used. Some UK based examples include the Mary Evans Picture Library specialising in historical images, and the Bridgeman Art Library.(3) Many national and university libraries also have extensive image collections which they are making available to students, researchers and commercial parties (although there are often charges for the service).

A great source of historical images with no known copyright restrictions can be found on the Flickr website: http://www.flickr.com/commons/ Their Creative Commons area is a project making freely available content from museums and galleries across the world. They also encourage tagging of the

images to increase information available about the content.

The Ley, Woebley (4)

Licences

For images which have previously appeared in print or online, it is usually the publisher who can advise on who the copyright holder is, and how permission to reproduce an image can be obtained. The originator of an image might have transferred copyright to a publisher permanently, usually termed ‘assigning copyright’, or they might have granted permission for it to be used only in a specific publication in which case it is referred to as granting a licence.

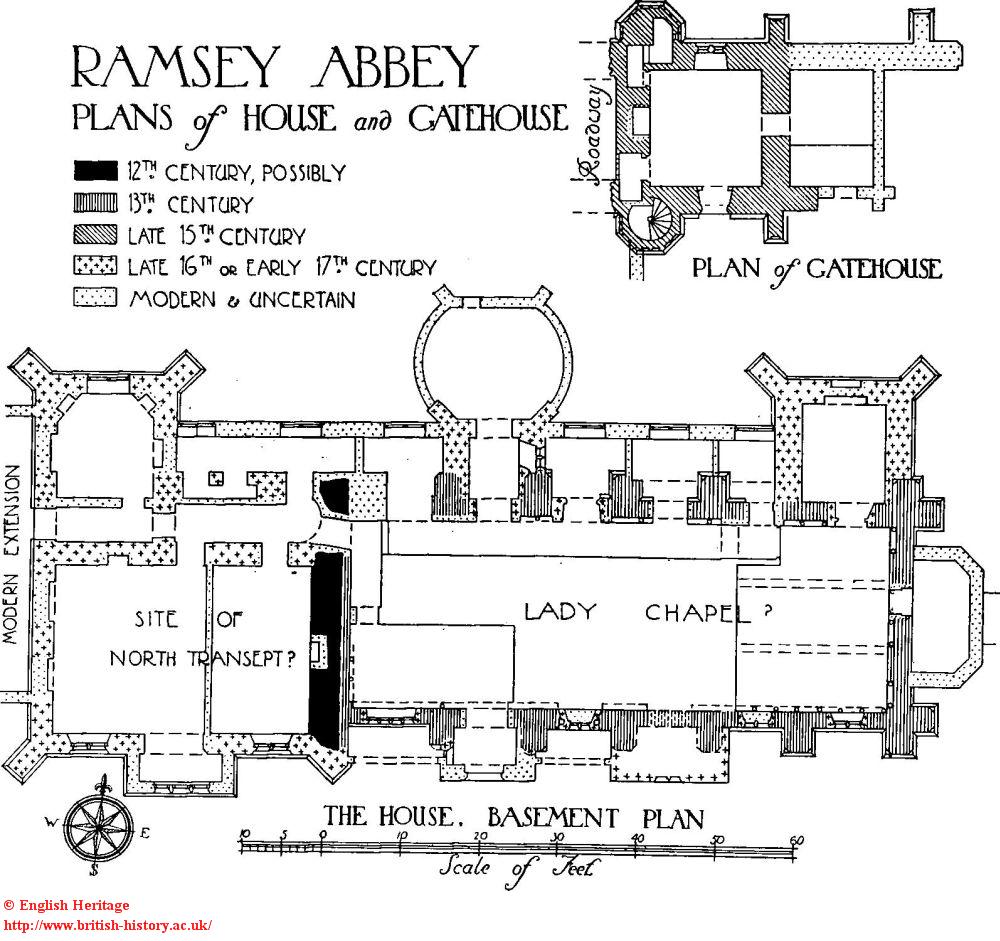

Licences to use images in publications including online projects will state where and how images can be used. So for example to illustrate this article I can use an image which is now owned by English Heritage, as they have given us permission to use images to promote the digitisation of the RCHME volumes. I could also use any images which are now out of copyright. I cannot use images in this post which have been cleared for use in the volumes by outside parties as permission does not extend to any other use of the image.

(5)

1. Lammerside Castle, Wharton. Royal Commission on Historic Monuments of England, Westmorland (1936) plate 80 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=120920 retrieved 23/2/2013

2. http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/copyright retrieved 7/12/12

3. http://www.bridgemanart.com/ http://www.maryevans.com/

4. The Ley, Woebley. Royal Commissions on the Historical Monuments of England, Herefordshire: Volume 3 North West (1934) plate 176 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=124854 retrieved 23/2/2013

5. Plan of Ramsey Abbey. Royal Commissions on the Historical Monuments of England, Huntingdonshire (1926) p. 208 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=123804 retrieved 23/2/2013

Copyright and images - an introductory guide

Rachael Lazenby

I’ve recently been working on the project to digitise the inventory volumes of the Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England (RCHME). Some of the volumes are already live and can be accessed here.

My role has been to identify all images which were not provided by the Commission and seek permission to reuse them on British History Online. A full report on the methodology I devised for this work along with the results is freely available and is published here.

The work has touched upon many issues relating to copyright which are common when using images in research and so I thought it would be useful to explain some of the basics of copyright, how it affects images in particular, along with providing links to various resources available online.

Lammerside Castle, Wharton (1)

Definition of Copyright

Where better to start than with a definition of what copyright actually is:

the

exclusive and assignable legal right, given to the originator for a

fixed number of years, to print, publish, perform, film, or record

literary, artistic, or musical material (2)

A key feature of copyright is that it arises in a work the moment it is created by the originator. It does not have to be registered in the way that a patent might be for a process or a product. It is also important to note that ideas are not subject to copyright - it is the expression of ideas that is subject to copyright. This expression might be a photograph, a piece of text, a musical score or a painting. Copyright may be assigned by the originator to another party or waived by the copyright holder in certain circumstances.

Wherever an originator chooses to display or publish their work the copyright of the work remains with them unless they explicitly assign it to another party or until a fixed number of years have passed after their death. Copyright law varies country by country but in the UK a work remains in copyright until 70 years after the death of the creator at which point it passes into the public domain.

Misconceptions about the right to use images, especially those appearing online, abound. One of the most common is that if an image does not appear with the copyright symbol and a named copyright holder it is not protected by copyright law. Although such copyright notices can help identify a copyright holder, images without this symbol are still protected by copyright law. An image that is publicly accessible is still protected by copyright and an image being publicly accessible does not mean it is in the public domain. Copyright protects a work from any unauthorised use. Even if the reproduction of an image is not commercial, for example if it appears in a blog post, it is not legal without the permission of the originator.

Reproducing art and photographs

Cases involving paintings and drawings which are owned by museums can be complex. For example, should you wish to reproduce a photo of a painting by a living artist, you will have to gain permission from the artist, in addition to the permission of the organisation who owns the photo. It is frequently the case that photography is not permitted in museums and galleries, but if you have taken the photo yourself, and the composition is artistic and takes in more than just the painting itself, it may not be necessary to obtain permission. If an artist is deceased you may have to approach their estate for permission to reproduce an image if they have died within the last 70 years.

There are some organisations which specialise in sourcing paintings and drawings and for a fee will make available a high resolution scan of the work as well as arranging permission for an image to be used. Some UK based examples include the Mary Evans Picture Library specialising in historical images, and the Bridgeman Art Library.(3) Many national and university libraries also have extensive image collections which they are making available to students, researchers and commercial parties (although there are often charges for the service).

A great source of historical images with no known copyright restrictions can be found on the Flickr website: http://www.flickr.com/commons/ Their Creative Commons area is a project making freely available content from museums and galleries across the world. They also encourage tagging of the

images to increase information available about the content.

The Ley, Woebley (4)

Licences

For images which have previously appeared in print or online, it is usually the publisher who can advise on who the copyright holder is, and how permission to reproduce an image can be obtained. The originator of an image might have transferred copyright to a publisher permanently, usually termed ‘assigning copyright’, or they might have granted permission for it to be used only in a specific publication in which case it is referred to as granting a licence.

Licences to use images in publications including online projects will state where and how images can be used. So for example to illustrate this article I can use an image which is now owned by English Heritage, as they have given us permission to use images to promote the digitisation of the RCHME volumes. I could also use any images which are now out of copyright. I cannot use images in this post which have been cleared for use in the volumes by outside parties as permission does not extend to any other use of the image.

(5)

1. Lammerside Castle, Wharton. Royal Commission on Historic Monuments of England, Westmorland (1936) plate 80 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=120920 retrieved 23/2/2013

2. http://oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/copyright retrieved 7/12/12

3. http://www.bridgemanart.com/ http://www.maryevans.com/

4. The Ley, Woebley. Royal Commissions on the Historical Monuments of England, Herefordshire: Volume 3 North West (1934) plate 176 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=124854 retrieved 23/2/2013

5. Plan of Ramsey Abbey. Royal Commissions on the Historical Monuments of England, Huntingdonshire (1926) p. 208 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/report.aspx?compid=123804 retrieved 23/2/2013

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)

.png)

a.JPG)